The Boston Globe profiles harpist Maeve Gilchrist and Revels FRINGE

Reviews

06.12.2015

Celebrate the season of love with Revels FRINGE at Club Passim, featuring Sophie Michaux and Adam Simon!

Buy TicketsReviews

06.12.2015

By Jeremy D. Goodwin Globe Correspondent June 11, 2015

Maeve Gilchrist’s musical memories go back to when she was a very young girl in Edinburgh, eager to join in with the adults who frequently jammed on traditional Irish and Scottish music in her house. Born to an Irish mother and a Scottish father, both of whom were active in the city’s folk music circles, little Maeve would grab a fiddle and pretend to play along.

It wasn’t long before she knew her way around a different instrument, the harp. And it gave her a chance to join that musical conversation.

“There’s something to be said for folk music in general being the people’s music,” Gilchrist, 29, says in a telephone interview from the road. “It’s built to connect people. It’s a social musical form, and I love that. I think it’s wonderful how, if you get a different group of people together, the groove will be very different. There’s a magic to that to me.”

Her informal exposure left Gilchrist so steeped in the folk music of her homeland, she recalls, that when she did enroll in the City of Edinburgh Music School when she was about 10, although the focus was on classical piano, her teachers were eager to support her extracurricular musical interests. When her interests broadened to include jazz, the school worked that into her curriculum.

A full scholarship to Berklee College of Music brought her to the United States at 17, and she’s made it her business to take the harp into unfamiliar places ever since. She’s been a member of fiddle great Darol Anger’s group the Furies, recorded with artists ranging from Irish flutist Shannon Heaton to New York art-rockers My Brightest Diamond, and plays as a duo with dancer Nic Gareiss. She also teaches at Berklee.

For a show at Arts at the Armory on Sunday, she’ll pair for the first time with Sam Amidon, the Vermont-born musician with a penchant for reimagining Appalachian folk music by coloring it with electronics, new music, and his own crooked aesthetic.

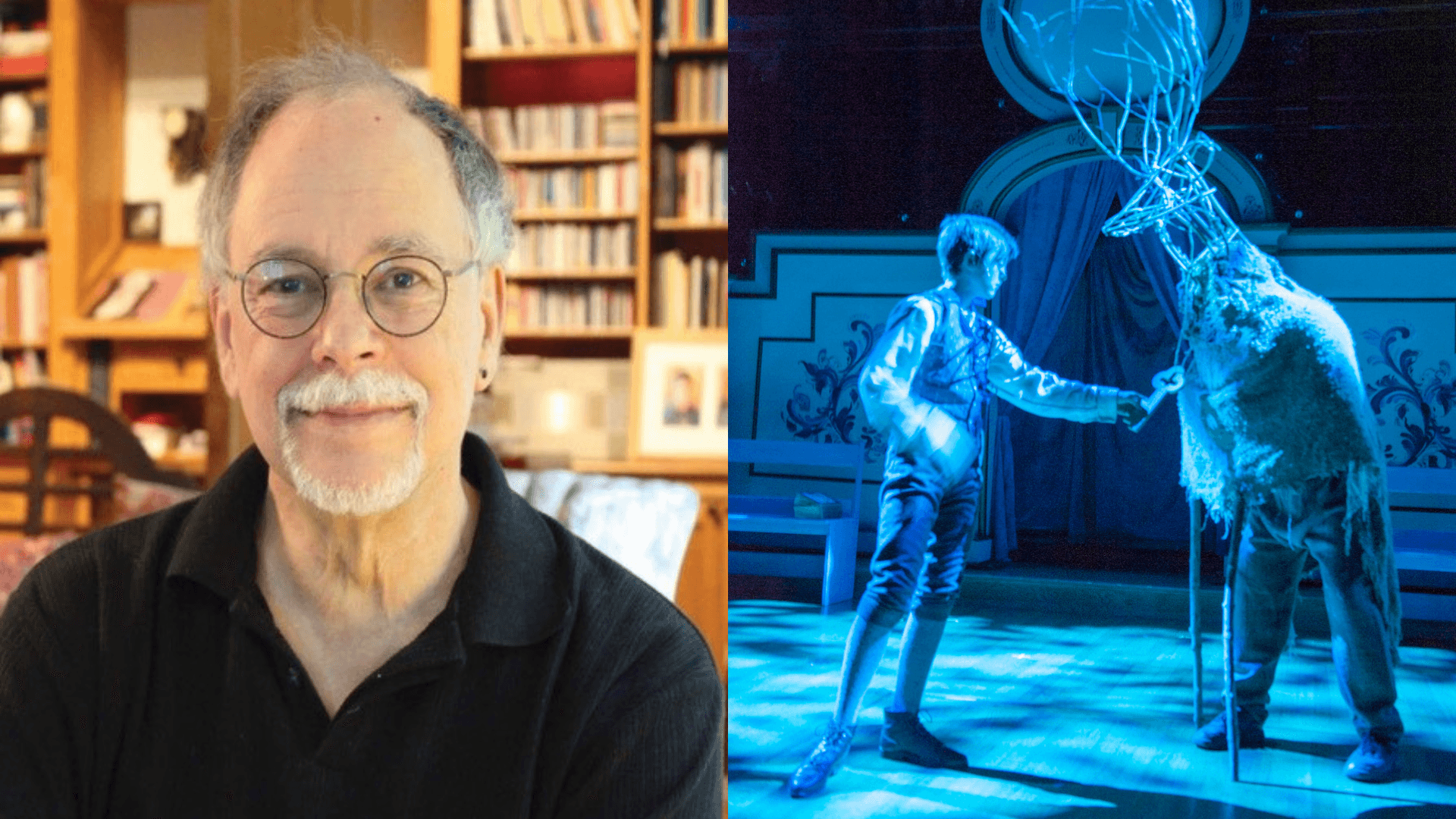

The two have never played together, but seemed a good fit for the latest in an occasional series of concerts dubbed Revels FRINGE, produced by the organization best known for “Christmas Revels,” an annual production drawing from cultures around the world. FRINGE sees the organization act as “a kind of dating service, putting musicians together who we think are really fascinating,” artistic director Patrick Swanson says. A concert last year featured Galician bagpiper Carlos Núñez Muñoz matched with guests including Gilchrist and jazz player Stan Strickland.

In a sense, pushing the clàrsach, or Celtic harp, into new territory is part of the instrument’s history. It has a different mechanism for creating sharps and flats than the pedal harp commonly used in European classical music. And while there’s a rich repertoire of traditional Irish music centered on the instrument, Gilchrist says, in the realm of Scottish music, harp players have frequently borrowed tunes written for the fiddle or bagpipe.

Harp can be a bit less portable than a fiddle, both in terms of carrying it around to impromptu jam sessions and finding common musical language with various styles of music. Gilchrist says that young harp players who receive only formal training can find themselves with a limited set of skills.

“It’s such a pleasing timbre that people are happy with very little,” she says. “You could sit at the harp and run your finger up, and it would sound very beautiful. So it’s very easy to make pleasing sounds and get away with very little. Harp players spend so much time playing by themselves and practicing by themselves in a room, they get scared of creating music with other folks, and it takes a little bit of a leap of faith to start doing that.”

She contrasts her own style with “this kind of mist-cloud, ethereal harping” that may come to mind for many listeners when they think of the instrument.

Amidon notes that he and Gilchrist have not yet met in person, but he is interested in her progressive views. “The harp has a lot of possibilities as an instrument,” he writes in an e-mail, “and I’m super excited to hear what Maeve does, and for us to make some music together. I really don’t know where it’s all going to go!“

Gilchrist says the combo has potential. “I suspect in many ways we come from quite similar musical places in regard to the strong presence of tradition in our music and the curiosity in contemporary sounds,” she says.

As for her own genre-hopping, the variety suits her. “My musical ADD has served me well,” she says.

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More